Most of us are probably familiar with the occasional mid-night voyage to a drive-through window to quell the munchies. Well, one small species of bat takes the concept of long-distance moonlit foraging to whole other level.

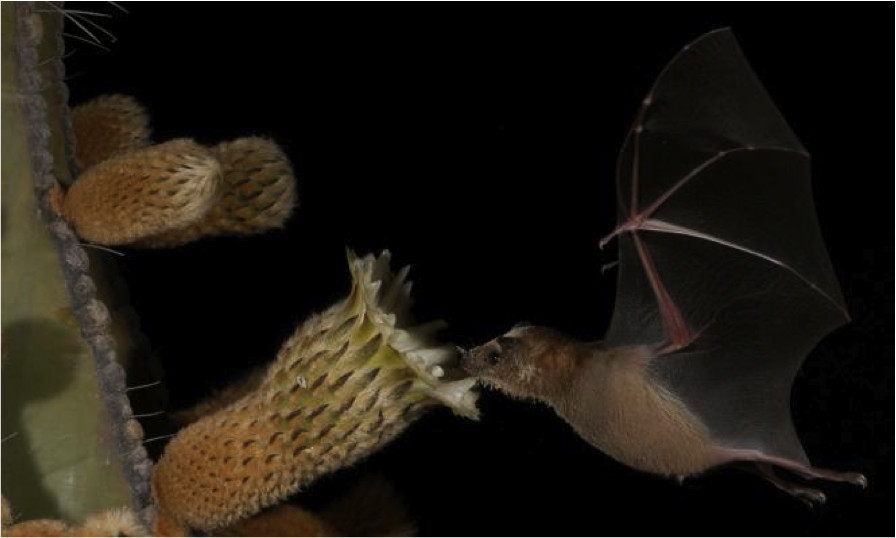

Lesser long-nosed bats (Leptonycteris yerbabuenae) are native to a large swath of territory that takes up much of Mexico, and parts of southern California, Arizona, and New Mexico. They are nectivorous, mostly eating the nectar of night-blooming desert plants like saguaro and organ pipe cactus, as well as agave.

In an unusual study, researchers have discovered that the bats travel as much as 100 kilometers (62 miles) in a single night in their quest for delicious cactus flower nectar. Can you imagine driving that far for a Big Mac?

While most lesser long-nosed bats stay put throughout the year, some females from the north are migratory, spending winters down south and summers up in the Sonoran Desert, which stretches through northwestern Mexico and the American Southwest.

But until now, how and where the congregations of females use food resources in the desert have largely remained a mystery. It’s been a particularly intriguing question for scientists studying the bats at the largest maternity roost site in the Sonoran Desert since there doesn’t seem to be any major food sources for large numbers of bats for tens of kilometers in any direction.

“You come out of the cave and you look out, and there’s no food for the bats,” says Rodrigo Medellín, Senior Professor of Ecology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, and lead author on the new study, which was published recently in the Journal of Mammalogy.

The distance between the cave and the nearest cluster of columnar cacti seemed insurmountable, especially considering how small the bats are.

“We looked at a map of the reserve and pinpointed the nearest saguaro forest, and the nearest one is 40 km north, and there’s another one 50 km northeast. So we said, ‘That’s impossible. This is a 30-gram bat’,” explains Medellín, holding up his fingers to illustrate something the size of a billiard ball.

Glow-in-the-dark bats

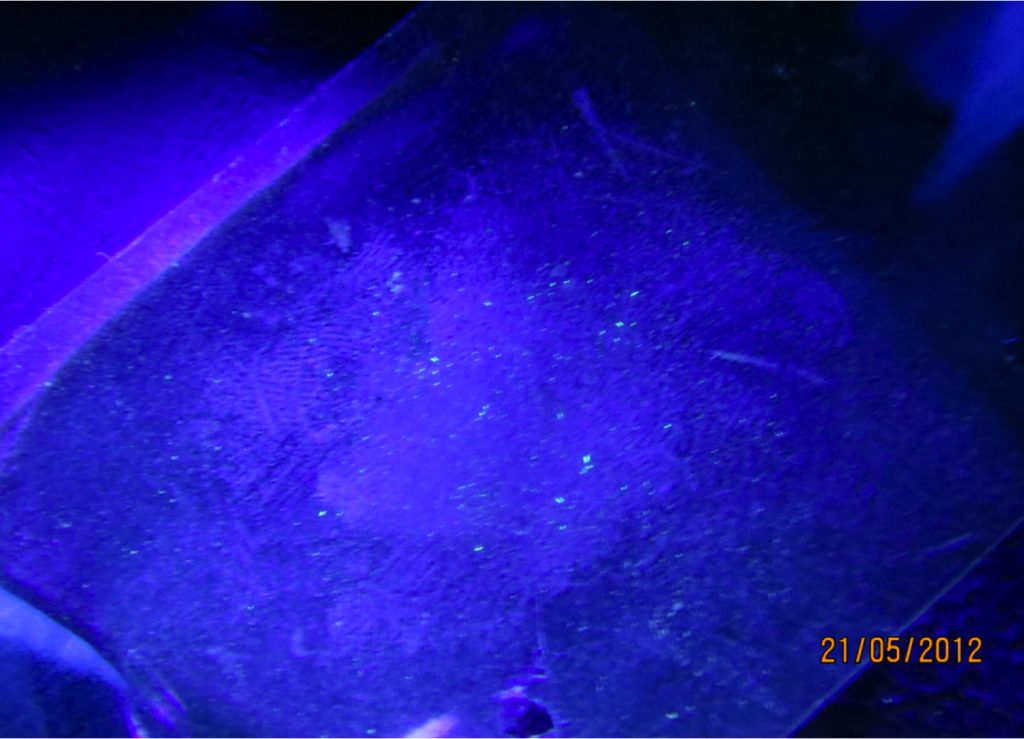

Was it really possible that the bats were making nightly round-trips of more than 80 kilometers (50 miles) to and from foraging areas? To find out, Medellín and his team would need a way to track the bats from the cave and see if they were the same ones showing up at the saguaro stands. The researchers employed a straightforward, but incredibly creative technique: sprinkling the emerging bats with a harmless, UV fluorescent powder, then capturing bats at the foraging grounds to see if they glowed under a UV flashlight, revealing their origin back at the cave.

Using a colander, the team sprinkled the fluorescent powder on the stream of bats flowing out of the cave at the beginning of the night. Then, teams at the two saguaro forest locations waited for the bats to show up. There, they caught bats in mist nets set near saguaros with freshly opened flowers and shone a UV light on them to see any glowing, glittery powder. Finally, before releasing them, the researchers rubbed a different color fluorescent powder on the bats. If the second powder turned up in any droppings on the cave floor of the maternal roost, it would confirm that the bats made the round-trip home.

Medellín says he and the team got their answer very quickly.

“The bats left the cave at around 8 pm. At around 10:15 or 10:20, they’d call me on my cell phone from 50 km away saying ‘We got the first bat, and it has the powder.’ And I go ‘What?!’ and of course we do a little dance there in the desert. This was immediate gratification to the thing we were trying to prove,” recounts Medellín.

Not only did the bats show up at both saguaro sites, but the team also found the second fluorescent powder in the feces back at the roost, confirming that these bats can move at least 100 km in a single night—the longest known nightly flight of any foraging, nectar-feeding bat.

Back from the brink

Until very recently, lesser long-nosed bats were listed as “endangered” under the United States’ Endangered Species Act and “threatened” under Mexico’s equivalent list. The bats were highly susceptible to disturbances in their caves from illegal drug traffickers along the border, recreational explorers and vandals. But thanks to conservation efforts, lesser long-nosed bats were removed from Mexico’s list in 2011 and the U.S.’s list just a couple months ago.

Though these flower-sippers seem to be on the mend, ongoing conservation work depends on knowing not only the numbers of bats in caves, but the movements and behavior of the bats.

Part of this study was seeing where the bats were feeding, but another important piece of the puzzle was determining the bats’ flight power and range. This is because scientists still know very little about the movements of the migratory females in this northern part of the bats’ range.

The discovery changes the game for understanding this migration by modifying what scientists consider the species’ limitations. Since the bats are so small, scientists have been looking for “stepping stone” caves every 20 or 30 km. A 100 km nightly range expands the scale at which researchers look for these pit stops along the way.

“This is going to help us pinpoint in a much more accurate way what the bats are doing on their way up and on their way down,” says Medellín.

This revelation also will better inform conservation work surrounding lesser long-nosed bats.

“The species has recovered, but that does not mean it’s completely out of the woods yet,” cautions Medellín.

A big determining factor of the long-term health of lesser long-nosed bats is the preservation of encouragement of nectar sources. If the bats can forage further from the roost than thought, then that means that bat-focused conservation practices (like the promotion of bat-friendly tequila) could be conducted in places previously considered too far from roosts.

So remember, if you do find yourself heading out into the dark to cure to an early morning craving, just be thankful you don’t have to be like the lesser long-nosed bat and trek what would be the equivalent of 680 miles one way just to nab a snack.