In the popular Alien sci-fi film franchise, the titular species—known as the “xenomorph”—targets hapless humans, often horrifically implanting their bodies with its own eggs. When the eggs hatch, the young emerge explosively from their unwilling incubator, with invariably fatal results for the human host.

The jarring life cycle seems like something cooked up entirely in fiction, but xenomorph reproduction was inspired by real animals living here on Earth—parasitoid wasps. These remarkable insects have used their bizarre reproductive method to quietly embed themselves in the lives of a dazzling array of invertebrate species, and have become arguably one of the most important insect groups on the planet.

Insects Turned Incubators

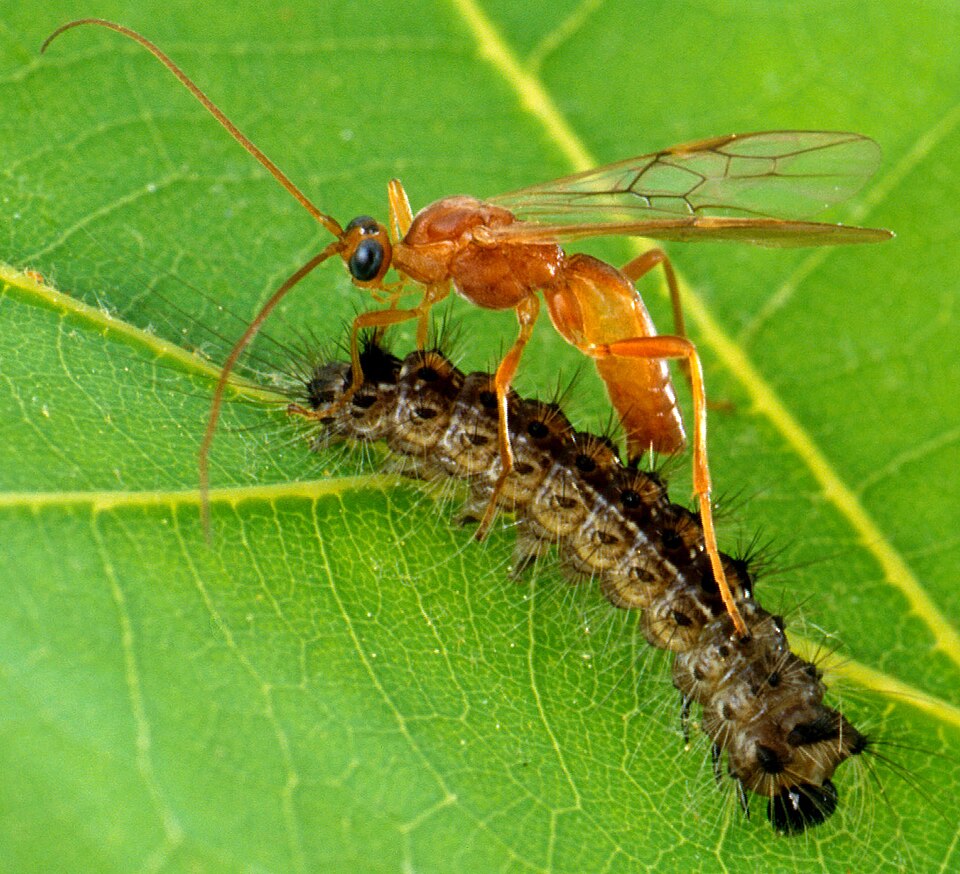

Like xenomorphs, parasitoid wasps use other animals (often other insects or spiders) as a food source for their young, typically keeping the victim alive for the whole disturbing process.

Some species are endoparasitoids, which inject a fertilized egg straight into the body of a host. The larva hatches, grows and feeds inside the still-living host. In contrast, ectoparasitoids will target a host, stinging it with a paralytic venom to render it completely helpless. They then lay an egg(s) on the outside of the host’s immobile body, and the hatched young feed on their paralyzed host. Either way, parasitoid hosts almost always end up dead at the conclusion of this wasp-rearing horror show.

The lethality of the strategy is what distinguishes “parasitoid” wasps from true parasites, which don’t typically kill their hosts.

Parasitoid reproductive biology has paid dividends for these wasps, resulting in the evolution of an extraordinary variety of forms and weird life cycle traits.

Take for instance the velvet ants, which aren’t ants at all, but a unique family of parasitoid wasps (Mutillidae) that have flightless, furry, ant-like females. Renowned for their blindingly painful sting, they also go by the nickname “cow-killer” in North America.

Experts in Mind Control

Many parasitoid wasps make their own nests, but not the crypt-keeper wasp (Euderus set), first described by science just last year. Crypt-keeper wasps rely on gall wasps for that job. Gall wasps use plants to rear their larvae, inducing trees to create tough cysts (“galls”) around freshly-hatched larvae inside the plant tissue, protecting the larvae until it reaches adulthood.

Crypt-keeper wasps place their eggs inside these galls, and when their larvae hatch, they drill into the bodies of the ready-to-emerge adult gall wasp. Once inside, they take over their host’s mind, making them tunnel into the gall wall towards the outside world—something the crypt-keeper can’t do on its own. But the puppet master directs its puppet to make its tunnel too narrow at the very end, causing it to wedge in place with its head stuck at the exit. After eating the gall wasp’s insides, the adult crypt-keeper bursts out of its host’s head, flying off into the world in its place.

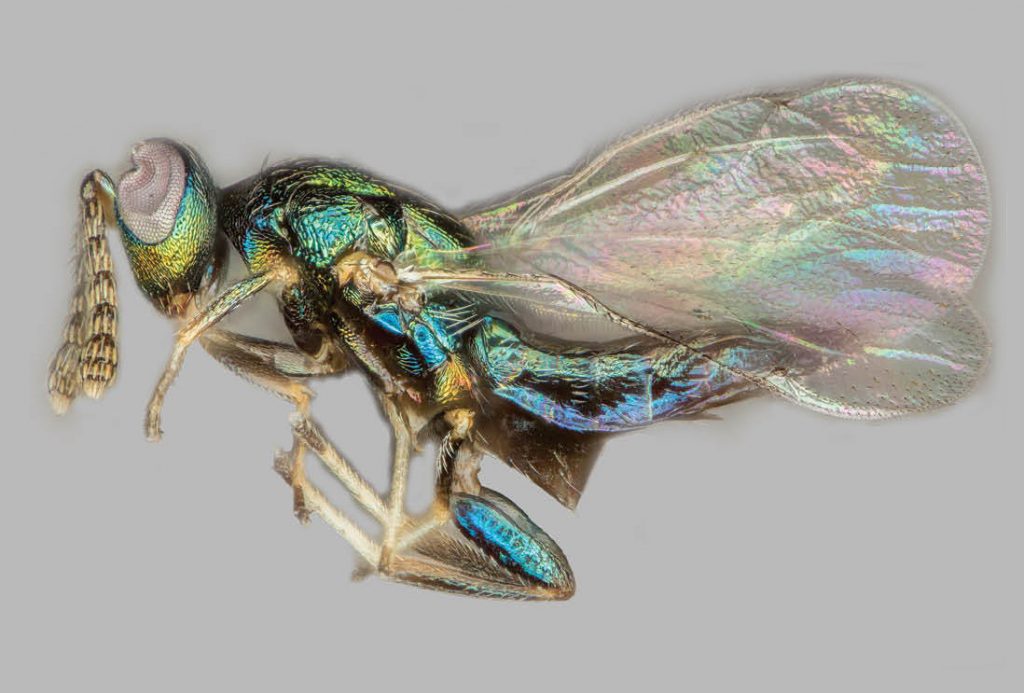

Crypt-keeper wasps are far from the only parasitoid wasps to dabble in mind control. Jewel wasps take over the brains of cockroaches with the help of a unique venom cocktail, injected right into the base of the head. The venom alters the roach’s mental state, allowing the jewel wasp to easily lead its many times larger victim into an underground tomb, where it lays an egg. Long after the wasp has left, the roach stays behind, drugged and unable to muster the will escape. It doesn’t take long for the larva to hatch and eat the cockroach, which remains fatally apathetic days after its capture.

The mind-numbing diversity of parasitoid wasps includes other oddities as well. There are giant, thumb-length “tarantula hawks” that exclusively target the big game version of spiders as baby food, and are armed with an excruciating (but medically harmless) sting. One species of parasitoid wasp new to science this year apparently rips its way out of its host using a sharp saw on its back.

It’s Their World, We Just Live In It

Since the diversity of host types is so broad, and so many parasitoids target a single species, the species diversity is off the charts, potentially numbering near a million species. Parasitoid wasps are probably the most species-rich animal group on the planet, far more so than beetles, which were long thought to hold the title.

A single type of insect host can fall victim to literally dozens of different parasitoid wasp species, but they may be hard to notice from our perspective because so many species are incredibly small in size. In their own dark way, parasitoid wasps have become one of the most successful animals on Earth, and they’ve been doing so secretively for some 200 million years.

Parasitoid wasps got their humble start in the Jurassic period, probably as wood wasps that targeted wood-boring beetles as larval incubators. There are still parasitoid wasps that do this today. From there, the lifestyle branched out into everything from caterpillars, to spiders, to other wasps. The parasitoid strategy is actually fundamental to the legacy of all wasps, since the familiar bees, yellow jackets, and ants that you see today are thought to be descended from a parasitoid ancestor, and have since secondarily lost their Alien baby-making ways. Incredibly, despite all the different types of parasitoid wasps today, this reproductive method evolved just a single time at the dawn of the wasp family line.

This soft coup of Earth’s insect biodiversity has been hundreds of millions of years in the making, and science is just now starting to understand the magnitude of parasitoid wasps’ hold on ecosystems. As a constant, subtle source of insect death, parasitoid wasps may have ecological influences that have gone completely unappreciated. With hundreds of thousands of kinds of parasitoid wasps pulling the strings on millions of insect and arachnid species, it’s apparent that it’s their world, and we are just living in it.