Scientists have gained new insight into the evolutionary development of brain and nervous system tissue, after examining fossilized brain tissue from a Cambrian sea creature that lived in modern-day Greenland half a billion years ago.

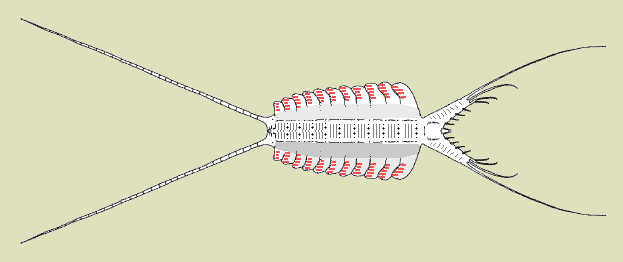

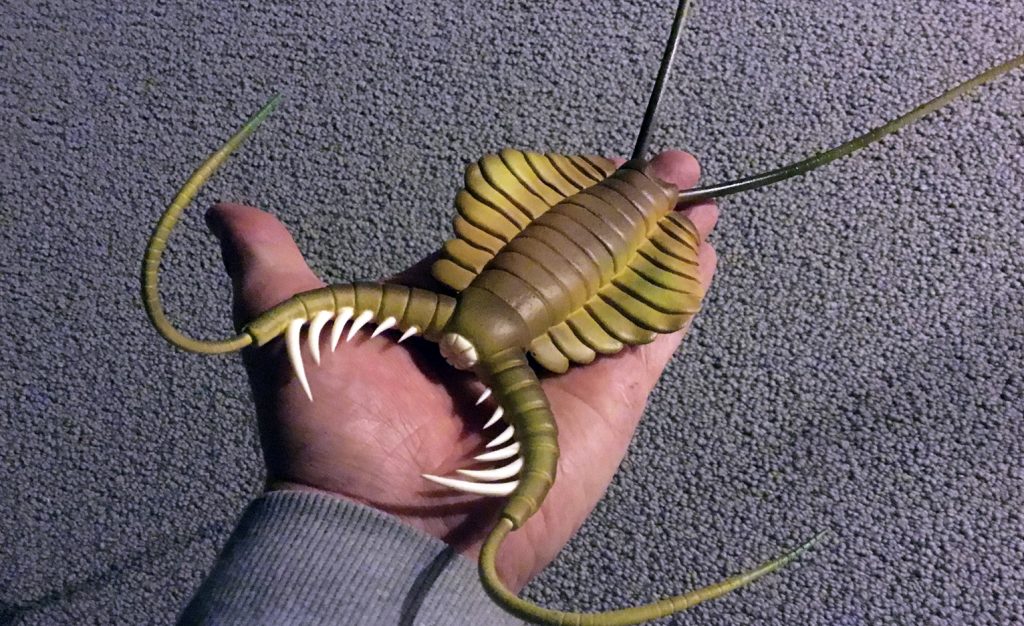

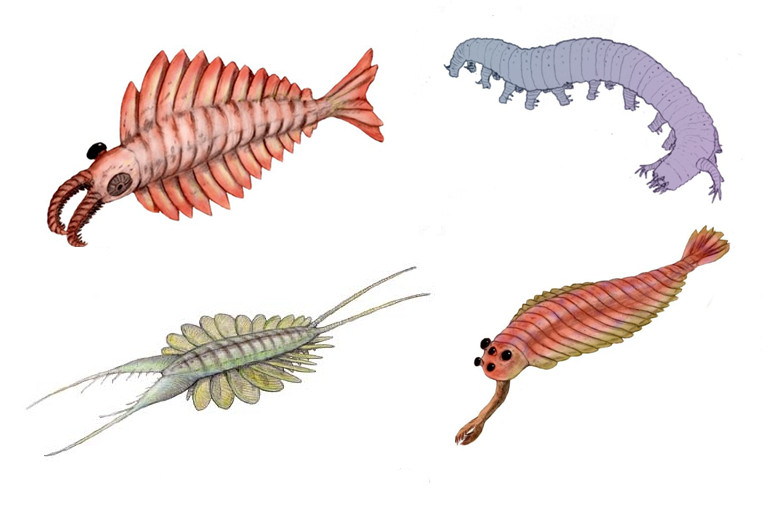

The extinct species, Kerygmachela kierkegaardi, was a predator with a long, spiny tail and front appendages used to grab prey. At its largest, it was about 10 inches long, but its size made it no less fearsome to other animals.

The 15 fossils uncovered in Greenland were unexposed to the elements, meaning they contain undisturbed, fossilized nervous tissue. It’s the first time scientists have gotten a firsthand view into the brains of panarthropods, the group that contains Kerygmachela kierkegaardi, plus crustaceans and bugs.

The team of researchers from Korea Polar Research Institute, the Korean University of Science and Technology, Oxford University, Durham University, the University of Bristol, and the University of Copenhagen, found that Kerygmachela kierkegaardi, considered the common ancestor of its animal group, did not have the three-part brain associated with complex mental development. The study was published last month in the journal Nature Communications.

Modern arthropods (crustaceans and insects) develop three-segment brains, beginning with a bundle of nerve cells located above the gut. Eventually, two other segments develop and fuse with the first.

Kerygmachela kierkegaardi only had the first, nerve-cell bundle segment.

The team compared Kerygmachela kierkegaardi’s brain to that of tardigrades (the microscopic creatures commonly called “water bears”), but other scientists remain skeptical, unwilling to say definitively whether the brains of tardigrades – or any panarthropods, for that matter – develop in segments.

WATCH NEXT: Great White Shark Attacks Inflatable Boat