Sudan, the last male northern white rhino — and perhaps the most famous rhino in the world — died on Monday, leaving his subspecies one step closer to extinction.

He was 45 years old and had been suffering from age-related health issues and infections that left him unable to stand, causing his keepers to make the difficult decision to euthanize him.

Sudan and the two remaining females, Najin and Fatu, had been living under the protection of a 24-hour armed guard in a special facility at Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya. As the last three of their kind, conservationists had once hoped that they might help reverse the fate of the northern white rhinos by reproducing naturally. However, it soon became clear that in his old age, Sudan wasn’t up to the task, and both Najin and Fatu are incapable of natural reproduction.

Still, as dire as the situation appears to be, all isn’t lost.

Armed with the latest in reproductive technology (and some of Sudan’s DNA), a dedicated team of veterinarians, conservationists and wildlife managers from the Czech Republic, Kenya, United Kingdom and South Africa is working hard to save the subspecies. To do that, they’re turning to another set of rhinos.

Looking to the South

While northern white rhinos sit on the brink of extinction, their closest relative, the southern white rhino, is thriving. And their burgeoning numbers — now in excess of 20,000 animals scattered in private game reserves and protected areas in seven African countries— are testament to the power of unwavering conservation. Only a little over a hundred years ago, fewer than 100 of them remained.

But the southern white rhinos had something the northern white rhinos lack: young, healthy females. So to save the northern white rhino, scientists are hoping to repurpose in vitro fertilization technology to turn their cousins into surrogates.

The plan appears deceptively simple — after all, we’ve been having human babies in a similar manner since the 1980s. But performing IVF with a rhino is much harder than with people, explained Jan Stejskal, Director of International Projects with the Dvůr Králové Zoo in the Czech Republic, one of the institutions leading the conservation project.

The male side is relatively easy. Scientists already have sperm from multiple rhinos on ice. But the hold up has been with the female end of things.

No one knew how to safely and successfully extract rhino oocytes (eggs), for starters. European zoos have been working with non-reproductive southern white rhino females to figure out how to do that.

“You can never be 100 percent sure, but we’re convinced that the technique to harvest the oocytes is optimized enough to attempt to harvest from the last of the northern white rhino females,” said Stejskal.

But, “there is only one laboratory anywhere in the world that has succeeded in getting eggs to the early stages of an embryo,” Stejskal explained—and it’s in Cremona, Italy. So immediately after the eggs are harvested, they need to be raced to Europe. “We have maybe up to 48 hours, but shorter is better.”

And for now, a mountain of paperwork lies between those precious eggs and the only lab on the planet that can fertilize them successfully.

You can’t just ship parts of critically endangered species wherever you like. Transporting these eggs between countries, let alone continents, requires a myriad of permits which have yet to come through.

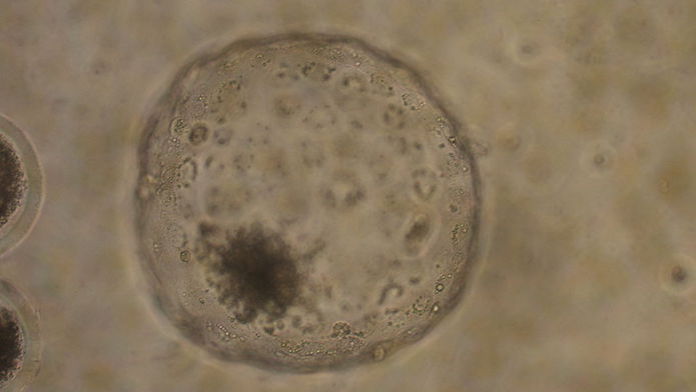

Even if those were approved tomorrow, though, it might still be some time before the eggs are collected because the researchers in Italy haven’t actually succeeded in getting fertilized rhino eggs to mature to what’s called the blastocyst stage, which is when they can be frozen until they’re implanted. But luckily, “they are very near,” said Stejskal, so he doesn’t think it’ll be long.

Test Tube Rhinos

Despite the hard work of many people around the world, the future of the northern white rhino remains uncertain. Assuming the embryos can be made, the chances of the surrogacy working are “still slim,” said Stejskal. Even in our species, IVF doesn’t always take, and in wild animals, successful implantation and gestation rates are even lower.

“We can’t expect that from the first, second, or third embryo we transfer to the mother, we would get a newborn baby,” he said. “That would be a miracle.”

And one or two babies isn’t going to cut it. To get to a point where the northern white rhino can be reintroduced, Stejskal and his colleagues will have to successfully produce many newborns.

“Even if I would be optimistic, I would say it won’t happen in the next twenty years, or even fifty years.”

If the current plan fails, all is not lost. There’s still hope that future technology will be able to bring them back. “What we’re trying to do with these females is do our best to harvest the last oocytes that were, let’s say, ‘created by nature’” explained Stejskal. But tucked in the laboratories of zoos around the world are twelve stem cell lines from northern white rhinos. It’s possible that these cells can be used to produce eggs or sperm even after the last living rhino passes, but such a technique would take years to develop.

Stejskal and his colleagues don’t care what the odds are, or how long it takes. “I can’t say it’s granted that we’ll succeed, but I would say this has to be done,” he said, “not only because these are the last three white rhinos, but because humans are responsible for them disappearing from our planet.”

This feature article has been updated to reflect the death of Sudan, the last remaining male northern white rhinoceros.