The vibrant rainforests of Central and South America have no shortage of impressive predators.

Jaguars slink through the understory, caimans and anacondas patrol murky waterways, and venomous lancehead vipers wait coiled below the leaf litter. But one of the region’s most proficient and deadly hunters rains fear down from the balmy canopy: the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja).

Among eagles, the harpy eagle is unmistakable. Matte black on its back, with white to dingy gray feathers underneath and a fluffy crest of feathers on its head that it raises when threatened, there are few eagles it can be confused with. This is especially true when you consider its size. Weighing over 20 pounds with a wingspan of more than 7 feet, harpy eagles are caught in what is basically a three-way tie for the title of “world’s largest eagle” with the Steller’s sea eagle and the Philippine eagle.

Ranging from southern Mexico, through Central America to the Amazon, the harpy eagle is outfitted with a battery of adaptations that make it one of nature’s most impressive hunters.

Razor-sharp talons

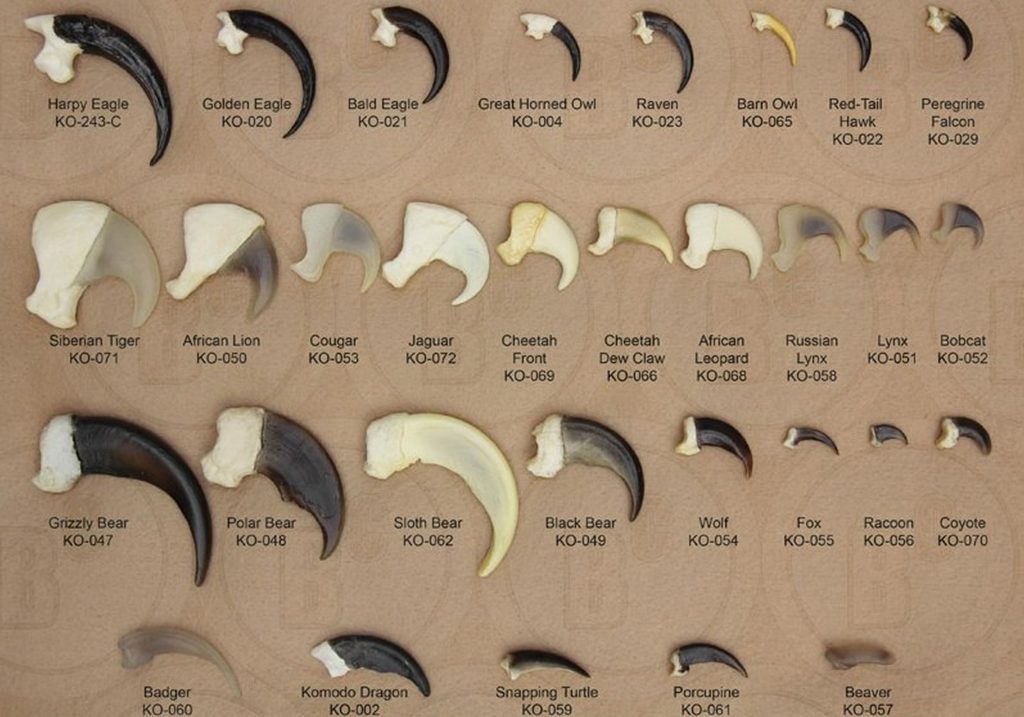

Perhaps the harpy eagle’s least subtle killing tool is its talons. Up close, these weapons are enough to disquiet even the most composed person. The feet on a large female are easily as large as a human hand, tipped with four almost comically long, black claws that unfurl into a dangerous grappling hook—the largest talons among any eagle. Growing up to five inches long, a harpy eagle’s claws are comparable to a grizzly bear’s.

These incredible contraptions have evolved for one purpose: ripping heavy animals out of trees, and not letting them go. The bulk of the harpy eagle’s diet consists of sloths and large monkeys, neither of which stray far from the middle reaches of rainforest trees.

The talons are connected to immensely powerful squeezing muscles, which crunch down on hapless prey like eight meat hooks driven by hydraulics. This ridiculous strength allows harpy eagles to snatch animals as heavy as themselves out of trees, sometimes without even stopping to land. They simply dive (sometimes at speeds approaching 50 mph), strike, and soar off with their prize, takeout style.

Specially-adapted wings

This brute strength is facilitated by their wings, which need to be powerful enough to provide lift for their giant meals. Harpy eagle wings are actually proportionally very short and wide for the bird’s size, and that broad wing surface helps provide the pushing power to stay aloft with their prey.

These wings also come in handy when navigating through the thick forest, which doesn’t leave a lot of room for flight. Shorter, broader wings give the harpy eagle unparalleled maneuverability in the tangle of branches and vines, allowing the raptor to dart and twist silently between canopies like a feathered fighter jet.

Supersenses

Harpy eagles—like most birds of prey—have an exquisite sensory array. Their eyesight is especially sharp, and their hearing is primed for even the smallest sounds. But harpy eagles have an adaptation for tracking prey that isn’t normally seen in day-active raptors.

Small feathers on their face can be erected to form a “facial disk” that helps funnel sound more efficiently into their ears. This disk is what gives owls—the super-hearers of the bird world—the characteristic “moon” shape of their face. It would appear that harpy eagles have partially evolved this device all on their own.

A historical connection

We can often use features of modern animals to help us understand the lifestyles of their extinct relatives, and the harpy eagle is a perfect example of this. Harpy eagles are large among living eagles, but they would have been downright puny set against the largest eagle of all time: the New Zealand’s Haast’s eagle, which could have weighed as much as 40 pounds and sported a 10-foot wingspan.

This real-life Roc likely hunted the island’s giant, flightless moa birds (and human inhabitants, once they arrived) until a few hundred years ago.

There are some key differences between the Haast’s and harpy eagles—not the least being size, as the Haast’s was about twice the size as the harpy. Haast’s eagles had skulls more like those of vultures, being low and long, and their talons—while large overall—were actually smaller for their size than those of harpy eagles. Haast’s eagles and harpy eagles aren’t especially close relatives within the eagle family tree; Haast’s closest living relatives are the teeny “hawk-eagles”, while harpy eagles belong to a small subfamily of large eagles found in the world’s tropics.

But the Haast’s eagle’s wings were incredibly similar to the short, wide wings of the harpy eagle. Given how the harpy eagle uses its own wings today, it’s possible that New Zealand’s extinct giant also flew through thick forest habitat and needed to capture and lift extremely heavy prey.

Today, thankfully, the harpy eagle is very much alive and is found over a vast jungle range in the Neotropics. However, the species is generally rare, and it has started to disappear from the northern parts of its range in Mexico. Harpy eagles prefer the types of pristine, rainforest habitats that are continually imperiled by human logging and mining activity. The harpy eagle is certainly an imposing and well-adapted predator, but it would do us good to remember that even honed “killing machines” can’t take on everything.