Asia is a continent of extremes. It’s home to Earth’s highest mountain range (the Himalayas) and one of the largest expanses of forest on the planet (Eastern Siberia’s vast taiga.) Plus, half of the world’s ten longest rivers are in Asia, including colossal waterways like the Yangtze, the Yellow, and Amur Rivers.

These huge river systems provide habitat to some of the world’s largest and strangest freshwater fishes, many of which have declined precipitously in population numbers in recent decade — making them rare to the point of near-mythic status.

Siberian taimen (Hucho taimen)

The Siberian taimen is a member of the salmon family native to northeastern Asia, with much of its current population residing in Mongolia and Russia’s Far East. Taimen look similar to the more broadly familiar salmon and steelhead trout, but don’t have an ocean-faring phase of their lifecycle, living entirely in the region’s remote rivers and lakes.

As the largest salmonid fish in the world, the Siberian taimen’s size is jarring. Some can reach six feet in length and weigh more than one hundred pounds. While this doesn’t make them the beefiest freshwater fish in the world, it does make them an imposing addition to their expansive, wind-swept drainages, where they terrorize the local fauna as apex predators.

If an animal fits in a taimen’s mouth, it’s food. Usually this means other fish — and other taimen, even — but rodents and waterfowl are fair game too. This carnivorous zeal has inspired their nickname as “river wolves” and attracted fly fishermen from around the world seeking an immense, voracious quarry to catch and release.

Their reputation as stream-bound terrors extends into the folklore of regional cultures, which often cast the creatures as having whale-like proportions, supernatural strength, and homicidal tendencies. Even today, tales of mysterious boat-sized fish in China’s Kanas Lake are thought to be exaggerations of a very real, possibly jumbo-sized population of taimen.

Unfortunately, the Siberian taimen—with their slow growth and delayed onset of sexual maturity—are more sensitive to human activity and harvesting than other salmonids. The species is now listed as “vulnerable” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), with most other species of taimen across Eurasia considered critically endangered. It’s thought that overexploitation and habitat degradation via gold mining and gravel extraction from rivers has driven the decline.

Kaluga (Huso dauricus)

The Siberian taimen of Russia and China’s Amur River share their watery home with another titanic fish — one big enough to casually inhale even the heftiest taimen as a snack. Meet the kaluga sturgeon, found only in the Amur basin.

While most sturgeon are renowned for their extreme sizes, kaluga are among the biggest, only slightly surpassed by their close European cousin: the 2,200 pound beluga (Huso huso.) However, the kaluga has a more predatory streak, using its tough, sharp teeth to tear into salmon, herring, pike, and just about any other fish unfortunate enough to get in its way.

This is an easy feat for the kaluga, considering it can grow to nearly 19 feet in length, and weigh more than a ton. This would automatically make it the most massive among wholly freshwater fish, but the species, like the beluga and many other sturgeon, doesn’t spend its whole life in freshwater, maturing at sea and returning to rivers to spawn.

These days, kaluga are on the verge of extinction, fished extensively (and often illegally) for their roe (eggs), which are coveted as caviar.

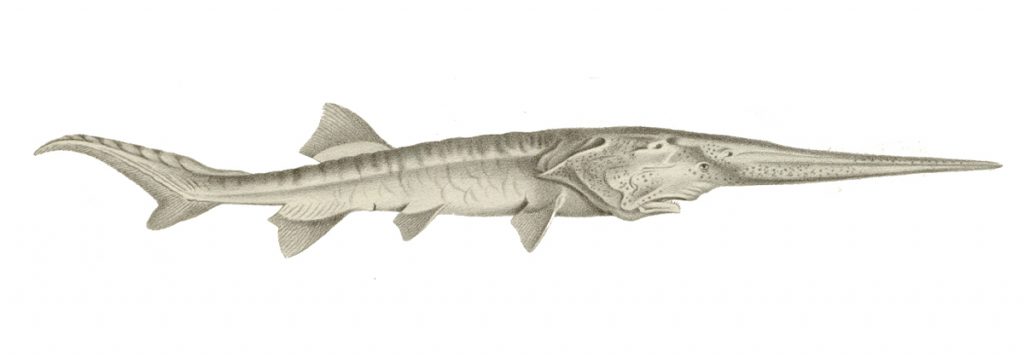

Chinese Paddlefish (Psephurus gladius

Paddlefish are relatives of sturgeon, and sport a distinctive paddle-shaped snout, lined with electroreceptors that help them find prey in murky environments.

Only two species have survived to modern times: the American paddlefish—native to the Mississippi River Basin—and the Chinese paddlefish, found only in the Yangtze River Basin. Chinese paddlefish differ from their American counterparts by having a proportionally longer and more blade-shaped “paddle,” making it more closely resemble a bizarre, deep-sea creature (like the goblin shark) than a river fish.

It’s also larger than the American species. Much, much larger. Unsubstantiated reports describe Chinese paddlefish stretching 23 feet long and weighing thousands of pounds. More reliable records place the maximum estimated size at ten to twelve feet, and several hundred pounds.

Unfortunately, little is known about their biology besides their general migratory habits; the fish hang out in the lower reaches of the Yangtze and its brackish estuary, but migrate upstream to spawn in the spring.

In fact, it’s this lifecycle that is partially responsible for why we know so little about them. In 1981, their migration route was blocked when the Gezhouba Dam was constructed in the middle of the Yangtze. This major impact, combined with many decades of development and overfishing, led to the near complete loss of the species by the early 2000s.

No live individuals have been seen in more than a decade, so the incredible fish may already be extinct. However, sonar-based hydroxacoustic surveys between 2006 and 2008 recorded signals that could easily have been from Chinese paddlefish, so there’s still some hope that the species lives on. If so, the Chinese paddlefish is likely the world’s rarest and most endangered giant freshwater fish.